Prince Edward County, Ontario, Canada

de Vries Natural Heritage Collection

September 09, 2017

By Terry Sprague

(excerpts given by Terry Sprague at the official fund raising launch)

I think it was around 1966, or so, when I first met Jake de Vries. He became aware of me through the column I had just started writing for the Picton Gazette and he invited me to his home at Rosehall, just northwest of Wellington, to see his bird collection. This I did, on the back of a Honda 150 motorcycle. I recall that Jake was quite amused by this, in as much as it was late November when I made the trip.

I think what fascinated me the most was his ability to portray his subject in a pose that was natural to that species on a base that replicated its natural habitat.

I recalled him urging me to take the same course as he did, from the Northwestern School of Taxidermy, from Omaha, Nebraska. I chose a starling as my introductory specimen, acquired quite easily with no further explanation as to how, and came up with the saddest specimen you ever saw. I couldn’t get it to stand up since I had placed its legs so far back on its underbelly that it more closely resembled a pied-billed grebe than it did a starling. It was then, that I fully appreciated what a special gift this man had in preserving birds as though they were still very much alive. I considered myself to be pretty good at remembering birds by sight and by sound; so was Jake, but he had the added skill of capturing how they should look as mounted specimens – their pose, whether in flight, or shy and retiring, or conversely, feisty.

Jake once explained to me that he acquired these birds from a variety of sources – some from the Department of Lands and Forests (today’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry), which had been illegally hunted – others like waterfowl, he got from hunters, while still others he found at lighthouses where migrating birds had collided with the structures. Others, he said, were given to him by friends who had found them illegally shot – “these people never leave behind an address,” I recall him saying in that delightful Dutch accent that I remember so well.

As anyone can see by the specimens on display, he had a gift for doing all species – mammals, reptiles and amphibians, game animals, fish (which he said were always very time consuming to do) large birds, small birds. He even preserved a microscopic ruby-throated hummingbird once.

I have been so thrilled to be a part of the Jake de Vries Collection Group, in our efforts to ensure that The de Vries Natural Heritage Collection will continue to remain in the county, and intact, and that his legacy will live on. I think it is a fitting tribute to a man who had such a love for wildlife and such a gift for bringing these once lifeless creatures back to life.

“The Natural Heritage Collection is County’s Best Kept Secret! This is one of the best privately held natural heritage collections in all of Ontario.” This comes straight from staff at the Royal Ontario Museum!

A Visit to the deVries Natural Heritage Collection, Ameliasburgh Heritage Village

September 21, 2021

by Amy Bodman, Prince Edward County Field Naturalists

In mid-September, members of the PECFN and PEPtBO executives had the great fortune to attend a private tour of the newly-opened deVries Natural Heritage Collection, hosted by Terry Sprague, Jake deVries’ lifelong friend and Janice Hubbs, the on-site curator at the Ameliasburgh Heritage Village.

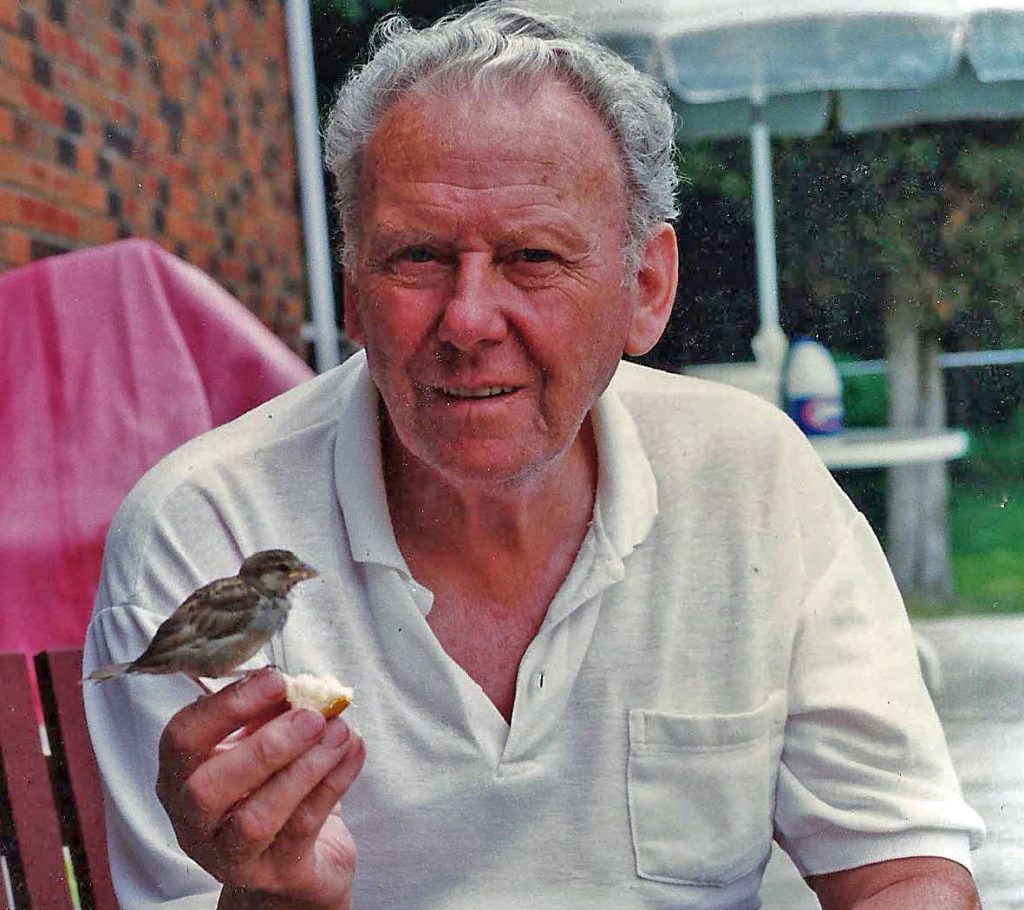

The collection features 50 years of work by the respected local taxidermist Jake deVries and contains over 220 different specimens of mammals, reptiles, birds and fish thoughtfully displayed to reflect their relationship to their environment wherever possible. After emigrating to Prince Edward County from Holland in 1948, Jake developed an interest in the songbirds of his new country. He eventually taught himself taxidermy by taking correspondence courses from the Northwestern School of Taxidermy in Omaha, Nebraska, earning a degree in 1960.

An enthusiastic conservationist, Jake saw taxidermy as a way to preserve and teach others about the value and beauty of nature. Terry pointed out that one extraordinary feature of Jake’s taxidermy work was his ability to set the specimens in lifelike poses that not only featured their beauty, but showed how they moved through and inhabited the natural world. Janice talked at length about the challenges of displaying such a variety of species in a manner that would pay homage to the artistry and intent of the work, as well as to Jake himself. She has done a wonderful job: one section features Jake’s life story and workshop, other sections are divided by habitat, type of animal and characteristic features. Fish and other aquatic species swim below the land and sky-bound animals. Special attention is paid to biodiversity and the interconnectedness of all living things. Janice, who along with Terry, was part of the committee responsible for finding a home for this extraordinary collection, is particularly proud to have it housed at the Ameliasburgh Heritage Village, expanding the notion of a “heritage” village to include the natural heritage that was (and still is!) a vital component of our daily life and survival.

Of the collection, Terry states: “Jake was such a close friend and had such a love for wildlife and for education. I get a bit upset sometimes when so many people view taxidermy with such distaste equating it with a morbid desire to flaunt everything as trophies of the kill. Jake wasn’t of that mindset at all and many a time I saw how upset he’d get when he’d show me a specimen and tell me how someone had shot it for no reason except to see it die. He wanted to see a wide representation of wildlife preserved and always opened his doors to school kids and the general public. I am so pleased that his tradition can continue, even after his passing.”